If Dr. Frankenstein worked with plants instead of bodies, he'd still have nothing on Temple University Ambler alumnus Brandon Huber.

Huber's collection of hundreds of plants sounds like something out of an herbology class at Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry. His home in North East Philadelphia and his home away from home at NC State are filled with all manner of carnivorous plants, spiny cacti of every shape and size and species a great deal more bizarre.

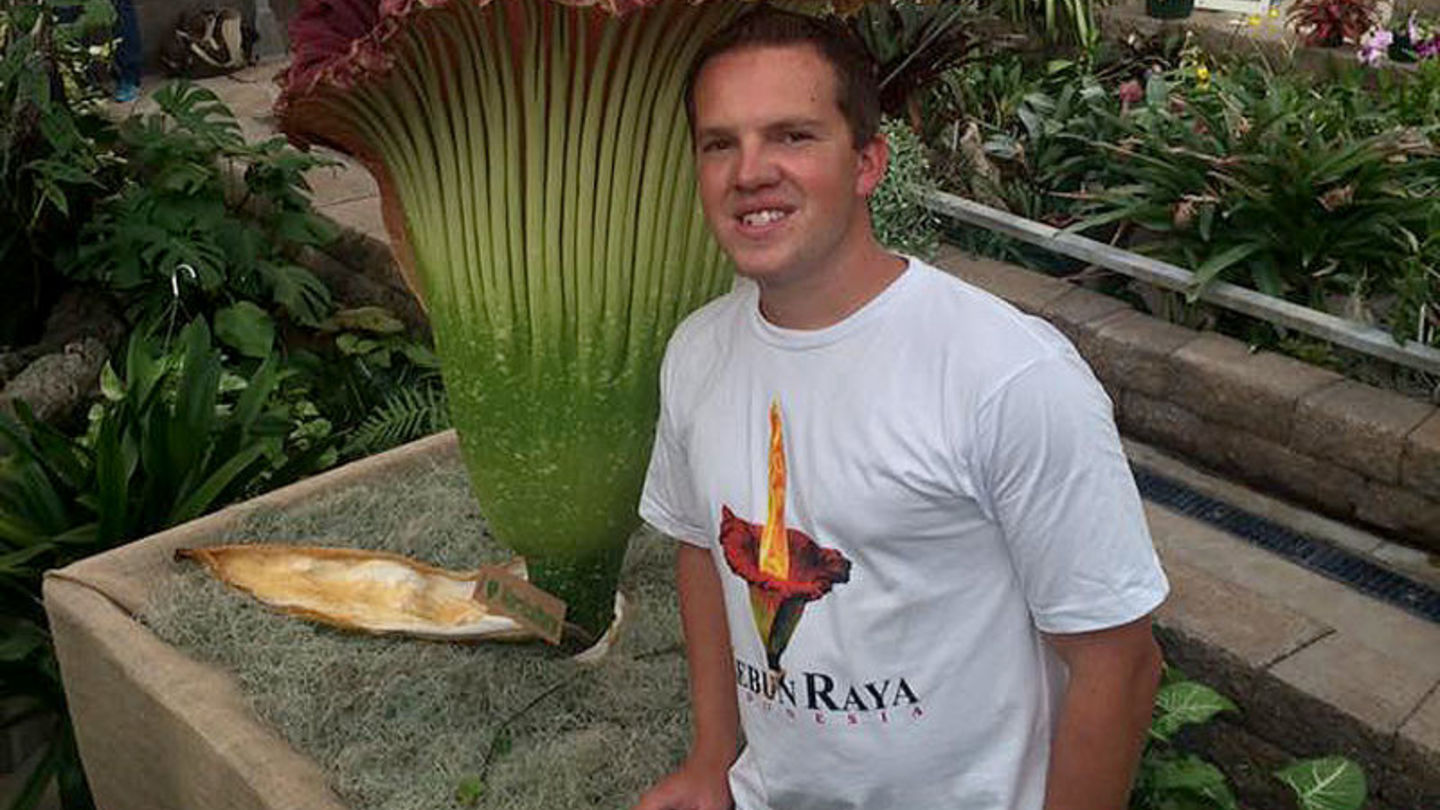

It's no wonder that his pride and joy, a 6-foot, 4-inch tall, 38-inch wide behemoth of a flowering plant — a 13-year-old Amorphophallus titanium — was named after a character in the famed series. The affectionately named "Lupin" recently bloomed, a rare occurrence welcomed by thousands of visitors to the greenhouse it currently calls home.

For Huber, who graduated with a B.S. in Horticulture from Temple in 2013, this was the culmination of years of preparation.

"The Amorphophallus titanium is the largest flowering species in the world. Before 2008, less than 200 were noted to have bloomed in cultivation in the world," said Huber, who is currently completing his master's degree in Horticultural Science at NC State. "There have been seven or eight that have bloomed in the past year, which is incredibly rare, but we have a better understanding of the plants than we've ever had before and there are a lot more shared resources available. It is still definitely not a plant your typical gardener is likely to grow — it needs a huge greenhouse space. People come out by the thousands to see them bloom and the bloom typically lasts only a couple of days!"

The rock star status of a blooming Amorphophallus is an interesting phenomenon considering it's more well known name, which it lives up to with noxious gusto — the corpse flower.

"The amorphophallus smells just like a dead body! It's actually a pollinating technique; just like other flowers use nice smells to attract bees and butterflies. The corpse plant attracts carrion beetles and house flies — anything that would be attracted to road kill," said Huber, who won a Best in Show Award in 2009 at the Philadelphia Flower Show for a smaller Amorphophallus konjac. "You'd think people would be repelled by it, but they can't get enough of it."

According to Huber, the Amorphophallus titanium is also "thermogenic; it actually heats up when it's blooming."

"It's a truly fascinating plant. It raises its temperature to nearly that of a human body to help attract its pollinators," he said. "The flower was about 90 degrees while it was inside a 75-degree greenhouse. We took some very interesting thermal photos in addition to collecting the remains of the bloom for study. Five years from now, I can expect another bloom!"

When Huber is not growing plants that nightmares are made of, he is focused on plant breeding. If he actually bred a man-eating plant, it wouldn't be much of a shocker, but for now his attention is firmly focused on developing new varieties of Stevia, a natural sugar substitute. His research is fully funded by PepsiCo.

"As a horticultural scientist this is most likely the type of work I would be doing professionally. I'm currently developing hybrids of Stevia that are high sugar and high yield with low bitterness," he said. "Stevia is not a true sugar; it is zero calories and safe for diabetics. The problem is, the taste just isn't quite there yet — a lot of people liken it to Sweet'N Low; they think it tastes artificial."

Huber said the goal is to find the right balance — the right compounds within the plants — between sweetness and bitterness."

"It's literally about finding the sweet spot. It's finding that one plant in a million," he said. "When I complete my master's my next step is to go on to get my PhD. I'd like to work for Pepsi while I complete my doctorate."

Huber will happily tell you he's been a "plant person" since his parents took him to the Philadelphia Flower Show when he was 8 — he now has more awards from the Flower Show than he has wall space. While truly in his element with his plants, Huber never wanted to remove people from the equation. At Temple University Ambler, he took on leadership roles, including president of the Ambler Campus Student Government Association. He was awarded the Ambler Campus Student Leader of the Year Award in 2013.

"Some plant people genuinely feel most comfortable in their gardens or greenhouses, surrounded by plants. They don't really like being placed in social settings and certainly avoid the spotlight — they're not 'people people,'" said Huber. "I saw that as a weakness in myself as well. Taking on leadership roles and public speaking was a real challenge. I knew I wanted to improve because I want to be a leader in the (green) industry."

To that end, he put his plant expertise — a combination of years of trial and error on his own and what he's learned in the classroom — to good use, giving talks to garden clubs and other organizations on a variety of horticultural topics in addition to working for years at the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society's Meadowbrook Farm while completing his undergraduate degree.

"I've knew I wanted to go to Temple since I was 14 — I went to an open house at Temple Ambler and said 'This is it!' The faculty were an inspiration and a wealth of knowledge and they were completely willing to give students the attention, help and guidance that they needed," Huber said. "I got more out of being part of the Ambler Campus community and student government than I ever could have imagined. Students can make an impact and you will see results."

Temple's horticulture program "was terrific in helping me build upon my existing knowledge, particularly the science of growing, plant physiology and chemistry."

"I want to be a plant breeder; that's always been my passion. I want to breed new plants — exotics that are even more bizarre and crazy, agricultural and ornamental plants that are more vigorous and disease resistant. In plant breeding, absolutely anything is possible and that's why it's so fascinating," he said. "Plants like the corpse flower or carnivorous pitcher plants or 1,000-pound pumpkins, they are like something out of fantasy, but they are real. They are the types of things you can show anyone — even people who aren't really interested in plants — and it's a 'Wow!' moment. I think that says a lot about horticulture and a lot about the diversity of the field."